The Dilution of Representation

This post on Best Of A Great Lot is a part of a series on the subject of designing a new form of governance. Each piece aims to stand alone, but fits together on the Table of Contents.

Representative government isn't something that scales particularly well, and we've been trying pretty hard for the past century or so to prove this.

There were 4 million people in the United States in the 1790 census. Today there are north of 330 million people, an almost 100 fold increase. This is often commented on, but it's even more extreme than it at first seems and causes more problems.

In particular, an unintuitive feature of scale change is that as the number of people in a group increases, the number of connections between people increases at a much faster rate (the square of, to be exact). A group of 10 people has 45 connections (possible pairings between people). We naturally want to assume that a group of 100 people will have around five hundred connections, but the math works out to be close to five thousand instead.

Organizations undergoing scale changes like this often fall apart or become unmanageable. Startups are the most common example of organizations that experience this sort of pain, and this challenge is notorious within the sector. Growing startups go through a number of stages, sometimes called scale points, where the size of the organization has changed enough that the people running the business need to step back and rethink how they communicate and how to operate well. The most well-known of these is Dunbar's number, around 150, which is a "cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships." Organizations that grow past 150 have to learn to function despite the fact that any particular person will not know everyone. More formal lines of communication and departments tend to be one example of how the organization has to work differently. One key change is that organizations often slide from determining promotions and responsibilities more from generally agreed merit either to more politics or more formal processes. This gets worse the larger the organization gets, and the largest organizations are well known to be tremendously political. For a certain kind of mind, either of these is a game to play. Employees are often forced to make a choice between the right thing and the promotable thing.

Scale matters to how we select representatives, one of the key elements of representative democracy. Imagine if we had a congressional district with only 150 people. At this scale it's possible to know all of the voters, and for them to know each other well. Picking the best representative in that context is a fairly straightforward exercise. It's possible as a citizen in this group to have a reasonable sense of the skills, capabilities and drawbacks of each possible candidate, and to make a reasoned choice. It's possible to make the representative feel social consequences if they vote in ways that are seriously at odds with the voters.

With a few thousand people, it's harder, though still possible. Someone running for office at this scale can meet a large percentage of their potential voters, and most people will know someone who knows a candidate directly. Many voters can spend time in close contact with candidates and thoroughly evaluate them, and it even makes sense to do so, as your change of affecting the outcome is reasonably large.

Somewhere in the tens of thousands of people, the dynamics of this changes in a way that emulates the change in companies. The behavior of representatives changes to follow the incentives that result. By the time you're into the hundreds of thousands, it's implausible that a candidate could know or even meet more than a small percentage of their constituents.

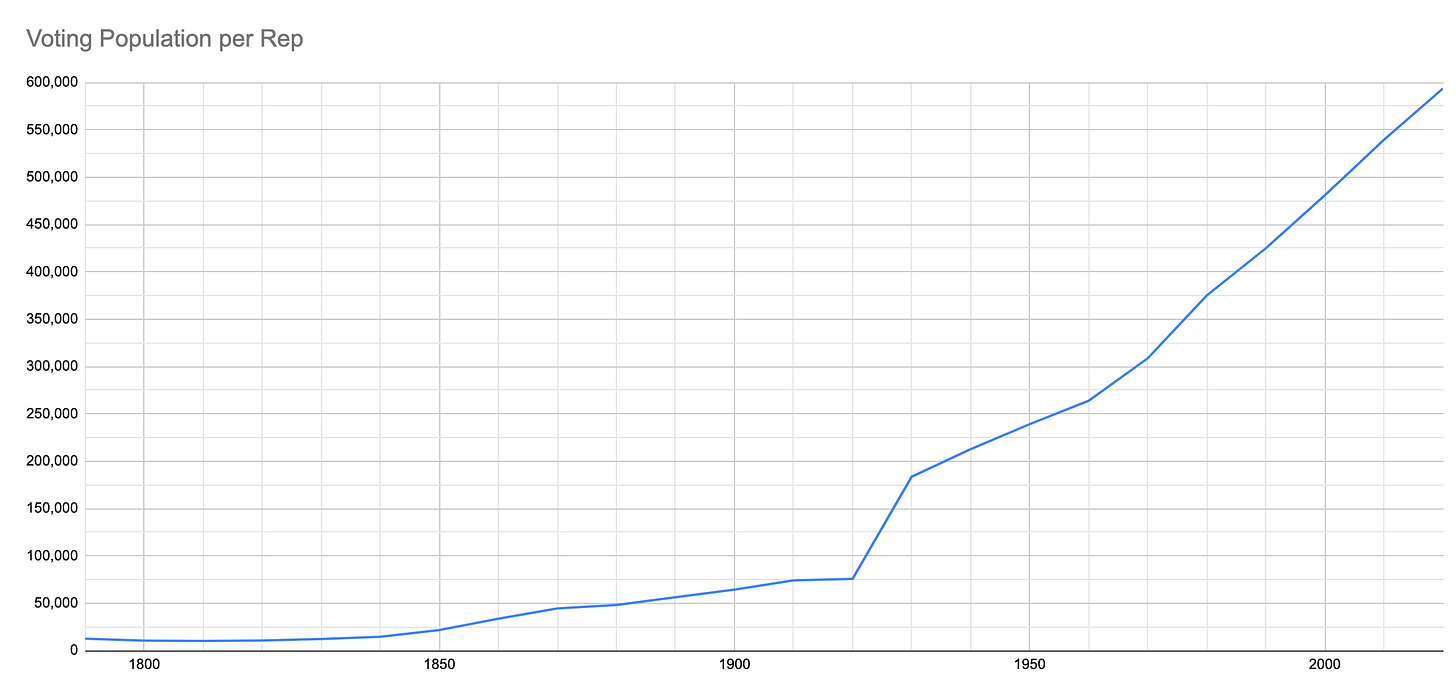

Here's a graph from the Pew Research Center showing the way that the number of people per representative has grown dramatically since the founding of the US.

But this graph, like so many considerations on this topic, reviews all population, not the people who can actually vote. When we discuss the way that scale has changed how representatives interact with the population, that's an essential aspect. Two major things changed from 1790 to today, resulting in a more extreme graph when considering voting population: 1) the expansion of suffrage, and 2) the reduction in youth as a portion of the population.

Of the 4 million people in the US counted in the 1790 census, 700,000 were slaves, and 1.5 million were women, neither of whom were allowed to vote. The population was also quite young, with nearly half under 16. So an additional 800,000 were free white boys who would be allowed to vote when they reached voting age, but weren't old enough yet. Compare that to today, when only 22% of the population is under 18. The total number of eligible voters in 1790 was less than 800,000.

I say less than because there are a lot more details of who could vote that reduce the total voting population then, but differ from state to state. In 1790 most states required you to own 50 acres of land to vote, but New York and Massachusetts only required you to have 40 pounds (about $7200 in 2022). New Jersey even allowed women (with property) to vote (until 1807). In addition, it's tough to get an exact count of men over 21, the voting age at the time, since the census counted people by under and over 16. The voting age was lowered to 18 in the 1940s.

In other words, if you were to delve into the details of this, at a state-by-state level, you'll find that the number of people who could vote in a given legislative district was mostly smaller than this for the first half century of America's existence. Early in the US's history, citizens had a much smaller pool of people to choose their representatives from, and could know them better.

The United States grew rapidly, and 50 years later, the total population was 17 million. With 2.5 million slaves, and a similar adult-to-child ratio. The voting population had grown to around 3.5 million. But that wasn't the only thing that had grown in those 40 years.

There were 67 representatives in 1790, for a maximum ratio of around 12,000 potential voters per representative (mostly lower). By 1840, Congress had grown to 242, and some states had removed landownership requirements, so the ratio had grown to around 13,000. In both cases, many races were won by candidates receiving only a few thousand votes.

Between 1840 and 1870, the first census after the official expansion of suffrage to include all black men, the ratio grew to around 40,000. To be clear, the end of slavery only accounted for a part of that. The US was growing fast through immigration in this period, and the size of Congress did not keep up. By 1900, despite a continuing increase in the number of seats in the House of Representatives, the number of voters per representative had grown to 100,000.

Then the 1920s happened. First women's suffrage doubled the voting population. Then, in 1929, because of political fears by rural citizens that newly immigrated urban dwellers were taking over the country, the House passed the Permanent Reapportionment Act, which fixed the size of the house at its current 435.

Voting population per representative. You can see the large jump in the 1920s after the 19th amendment, but you can also see the fairly flat line from 1790 through 1840 and the slow growth throughout the rest of the 19th century and the much faster growth in the 20th.

The previous graph showed an order of magnitude increase, from 50,000 to 500,000. That's a big increase. But when viewed through the lens of voters, the change from the first fifty years of the Republic to today is more than a factor of 50, from under 10,000 to 500,000. A voting population of ten thousand is a vastly different proposition, in both quantity and quality, from one of half a million. Candidates then could engage in retail politics at a level that a candidate today can never approach. Meeting with individual and small groups of voters and spending real time in the community is a fundamentally different thing from the professionally managed campaigns that primarily work through well organized machines and professional groups. A large voting body incentivizes much greater use of high technology and channels like unions and professional organizations to reach your potential voters. A small voting body means it's possible to get to know a larger portion of your citizens and what they care about, and possible for well-meaning representatives to do their best to truly represent them.

A corollary on the voter side is simply less reason to pay attention. If you know that your vote is one of half a million, it takes a lot of mythologizing democracy to spend much time on it. The chance that your vote will have an effect is very low, even if you're lucky enough to be in a district with a close race.

Similarly, unless you're a member of a legible bloc that your representative can interact with, it's unlikely that they'll do much work to understand your views.

It's a common argument among economists that a simple calculation of the value of your time shows that voting isn't worth it.(https://www.econedlink.org/resources/the-economics-of-voting-what-do-you-mean-my-vote-doesnt-count/). It's extremely unlikely that you specifically will change the outcome. But voting itself doesn't take nearly as much time as the work to develop an informed opinion about the candidates. This becomes less and less valuable as you know that your influence over the representative grows weaker because of the larger number of voters. On the representative side, understanding what your citizens want from you is a similarly more gestalt process at a larger scale.

So it shouldn't be surprising that a good portion of voters abstain from voting, and that of the rest, many are very poorly informed. The chances that anyone will be interested in their carefully cultivated views are low, and the chances that it will have an effect even lower. As voting scales, our close engagement with the process has every reason not to.